October 5, 2018

Air Date: October 5, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

EPA Raises Risks To Children’s Health?

View the page for this story

The Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Children’s Health Protection is tasked with keeping vulnerable kids safe from environmental exposures. But in September 2018, EPA placed the head of the office, Dr. Ruth Etzel, on administrative leave. Some are concerned that this is the first step in closing the office. They are also raising concerns about the EPA’s current effort to rollback mercury regulations, which is especially harm to infant and child development. Pediatrician and founding director of Boston College’s Global Public Health Initiative Philip Landrigan, MD helped put the EPA office of Children’s Health together decades ago and he joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about what these decisions could mean for the health of children. (06:55)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra also tells Host Steve Curwood about the Trump Administration’s attempt to roll back mercury rules for coal-burning power plants, and then launches into a discussion about regulating another notorious byproduct of the coal industry: coal ash. Then, he recounts a single day in the 19th century that brought some of the most devastating fires in American history. (03:47)

Cool Fix For A Hot Planet: A Tiny, Carbon-Sucking Fern

/ Anna GibbsView the page for this story

Fifty million years ago, Earth was a hothouse, with carbon dioxide levels nearly ten times what they are today. Then along came a tiny but fast-growing fern called Azolla. Within a million years it had pulled trillions of tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, cooling the Earth. Living on Earth’s Anna Gibbs explains how the carbon-fixing powers of Azolla might now be harnessed to help us cool the planet once again. (02:06)

Failed Tsunami Warnings

View the page for this story

On September 28th, 2018, an 18-foot tsunami struck the Indonesian coast, killing thousands and stranding survivors without any kind of assistance. A system of buoys meant to monitor for tsunamis has been nonoperational for some time, and a new, more advanced system of underwater sensors was nixed just days before the tsunami reached land. Louise Comfort, one of the lead researchers in the development of these sensors from the University of Pittsburgh, discusses her project with Host Steve Curwood. (05:40)

Walrus Changes His Mind

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Svalbard, Norway is home to a variety of Arctic life, some of which are quite intimidating. Living on Earth Explorer-in-Residence Mark Seth Lender recounts a close encounter with a large and wrinkled old walrus. (03:46)

Hemlock Trees On Hospice

/ Savannah ChristiansenView the page for this story

A novel science communication project called “Hemlock Hospice” is a collaborative work by Harvard Forest Senior Ecologist Aaron Ellison and artist David Buckley Borden. A series of installations along an interpretive trail in the 4,000-acre Harvard Forest in Petersham, Massachusetts relate the story of the vanishing eastern Hemlock tree. Climate change is spurring the Hemlock Wooly Adelgid, an invasive insect, to move further north, and it’s bringing down many Hemlock trees. Living on Earth’s Savannah Christiansen travelled there to talk to the team about the project. (07:09)

John Kerry Looks Back – And Ahead

View the page for this story

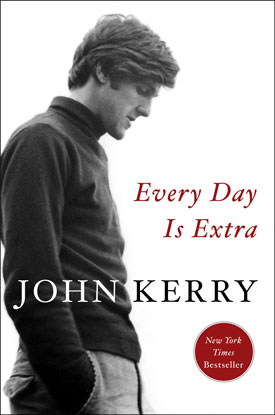

Former Secretary of State John Kerry is the author of a new bestselling book, called Every Day Is Extra. At its heart is a message of urgency about the need to address the climate crisis. Yet Kerry remains optimistic about the ability of the United States’ democratic system to tackle the most pressing global issues of today. In a conversation with Host Steve Curwood, Kerry discusses his longtime love of the ocean and concerns about ocean health, and says that what America needs now is for citizens to get out and campaign for politicians willing to move the country in the right direction. (15:07)

BirdNote®: Chipping Sparrows: Song Learning Starts Early

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

For anyone who has taken a moment to listen to birdsongs on a walk outside or has dropped a crumb on a sidewalk at lunch, the Chipping Sparrow is most likely a familiar sight. But scientists are still unlocking the secrets of this common bird. In this week’s BirdNote, Mary McCann gives us a closer look into recent research that shows how young Chipping Sparrows develop their signature songs. (01:55)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Louise Comfort, John Kerry, Philip Landrigan

REPORTERS: Savannah Christiansen, Peter Dykstra, Anna Gibbs, Mark Seth Lender, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

I'm Steve Curwood. John Kerry has led climate action as Secretary of State and presidential nominee, and he says don’t give up.

KERRY: There's no mystery to how we reclaim the direction and future of our country. It's by going out and working in our democracy. Make it work. And you can't do it sitting on your butt and pretending someone else is gonna do it or it's just not involved with you. We can change this. But we have to do it now, 'cause the clock is ticking.

CURWOOD: Also, using art to tell the story of losing the Eastern Hemlock.

ELLISON: Our forests are not static, fixed systems. We do need to keep in mind as we walk through the exhibition that the forest today, and the forest tomorrow and the forests 100 years ago or 50 years ago are all very different forests.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

EPA Raises Risks To Children’s Health?

Children are often more vulnerable to environmental toxins than adults. (Photo: KristyFaith, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Just as the Trump Administration announced plans to roll back mercury regulations for coal fired power plants, the Trump EPA also placed the head of its Office of Children’s Health Protection on administrative leave. Mercury can lead to brain damage in children, and the Obama era mercury rule also reduces enough soot and other pollutants to prevent more than 10,000 excess deaths a year among adults. With its director gone, the office of Children’s Health Protection is at risk of being closed altogether, and the EPA has already said it will close its office of scientific advisor. Pediatrician and epidemiologist Philip Landrigan is the founding director of the Global Health Initiative at Boston College and joins us now. Dr. Landrigan, welcome back to Living on Earth!

LANDRIGAN: Steve, it's good to be back with you. thank you.

CURWOOD: Dr. Ruth Etzel has been placed on administrative leave at the Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Children's Health Protection. What can we expect now that she's been placed on leave?

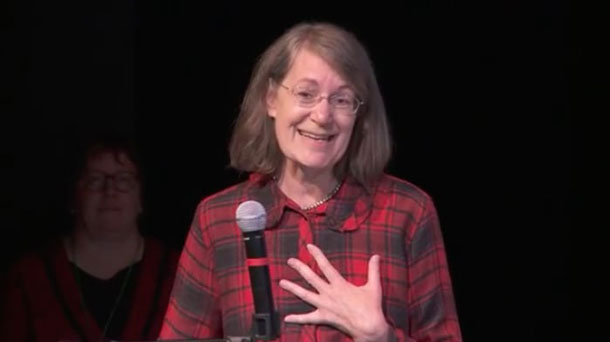

No clear reason has been offered for placing Dr. Ruth Etzel on administrative leave from her position as the head of the EPA’s Office of Children’s Health Protection. (Photo: Alaska Community Action on Toxics, YouTube)

LANDRIGAN: Well, she's a deeply knowledgeable person who brings an enormously deep skill set to this position. I'm afraid that the decision to place her on an on administrative leave may signal a decision by the Environmental Protection Agency in the present administration to deemphasize the protection of children's health.

CURWOOD: Often in a bureaucracy when some executive is put on administrative leave. It is a signal that they're concerned about wrongdoing. What's being said about Dr. Etzel in this case?

LANDRIGAN: Nothing has been said about wrongdoing. She was placed on administrative leave and no reason has been given.

CURWOOD: Recently, the EPA announced that it wants to loosen restrictions on the amount of mercury that can come out of coal fired power plants. It has me wondering if Dr. Etzel is being pushed to the side at the same time they've made this decision.

LANDRIGAN: Well, in recent weeks the Office of Children's Health Protection at EPA has been arguing against the rollback of mercury emissions standards, that the story here is that all coal contains little bits of mercury, and when you burn coal that mercury vapor rises and if you burn a lot of coal, the little bit of mercury that's in each ton adds up to a lot. That mercury goes out into the air. It comes down in rivers and lakes and the oceans. It gets into fish, and then when a pregnant woman or a young child eats that fish that is contaminated with mercury, the mercury goes right through into the baby and has been well documented to cause brain damage. It reduces the child's IQ. It can disrupt the child's behavior. This can be lasting injury that that is with a child for years and decades to come. Over the last decade, EPA worked very hard to put rules in place to reduce emissions or mercury from power plants. The Office of Children's Health Protection was very much involved in that process, arguing that mercury emissions needed to be controlled to protect the health of America's children, now and in the future. I think any effort to roll back those rules is fundamentally wrong. It's immoral and it's basically sacrificing America's future for somebody's short term profit.

Dr. Phil Landrigan is the Founding Director of the Children’s Environmental Health Center at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York City. (Photo: Courtesy of Phil Landrigan)

CURWOOD: And perhaps the reason that that Doctor Etzel is now on administrative leave for opposing that move.

LANDRIGAN: It would be possible, yes.

CURWOOD: Years ago, Dr. Leonard, you were involved in starting the Office of Children's Health Protection at the EPA. How do you feel about this decision?

LANDRIGAN: Well, I'm disappointed. I see the Office of Children's Health Protection as a vital watchdog within EPA. Children are a vital part of our population. They are five or ten percent of our population now, depending on which age group you use as the cutoff, but they are one 100 percent of our future. They're also an extremely vulnerable group within the population because of their biology. And they have no voice of their own. They count on us, the adults in the population to speak up for them and to protect them. So, I see walking away from the protection of children's health as being very damaging to America. I also think morally it's wrong. I think children deserve our special protection. But, even leaving that off the table, it's just not wise for the future health, stability, security of this country.

CURWOOD: Dr. Landrigan briefly what are some of the health risks of children that this office in particular has been protecting that we should be concerned about?

LANDRIGAN: Well, the initial focus of the office was to protect children against toxic pesticides, and it has insisted that the risk assessments within EPA incorporate what are called child protection safety factors into pesticide standards. They also encourage the air office, the air pollution office, to set air standards low enough that they protect children's health. The office has sought to protect children against lead and against mercury. It really covers a wide range of issues that have the potential to affect children's health.

CURWOOD: By the way the EPA is also looking to shut down its Office of the Science Adviser. Tell me please about some of the potential outcomes of this decision?

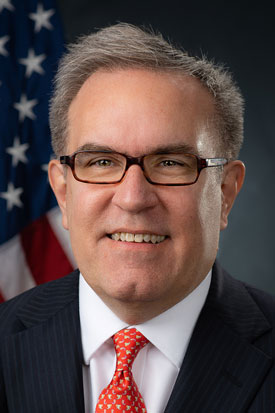

Under the direction of Acting EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler, the EPA is looking to weaken standards for coal-burning power plants that emit mercury. (Photo: United States Environmental Protection Agency, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

LANDRIGAN: Well, the science advisor like the office of children's health protection is a watchdog. It provides advice to the administrator and the senior staff. It guides them to make decisions that are based on evidence and based on science, as opposed to other factors such as short term political gain or profit. And if that office is dissolved then I would argue that EPA, which is supposed to be a science based organization, is going to be flying without a radar.

CURWOOD: Some would say it's about money. Industry doesn't like these regulations. It's costing them money.

LANDRIGAN: Yeah, various industries have pressed for many years to eliminate or at least weaken the Office of Children's Health Protection. I have no specific knowledge that an industry has intervened here, but certainly these actions are part of a consistent pattern that reflects industry's longstanding goal to eliminate or weaken the office.

CURWOOD: I have to ask how angry are you about this?

LANDRIGAN: I'm very angry. I mean, I'm a pediatrician. I've devoted my professional life to protecting children against environmental hazards. I'm also a father and a grandfather, and it really angers me to see very carefully crafted protections for children's health that have been put into place with meticulous care over the span of two decades being ripped away in a weekend.

CURWOOD: Philip Landrigan is the pediatrician an epidemiologist and founding director of the Global Public Health Initiative at Boston College. Dr. Landrigan, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

LANDRIGAN: Thank you, Steve. It was a pleasure.

Related links:

- NYTimes Opinion | “A Bad Move That Could End Up Exposing Kids to Chemicals”

- EPA | About the Office of Children’s Health Protection

- Dr. Ruth Etzel Biographical Information

- EPA | About the Office of the Science Advisor

[MUSIC: Dogs Of Desire (Albany Symphony)/David Alan Miller, “Last Call At the Folies Bergere (Outro)” on The Wild & amp; Whimsical Worlds of David Mallamud, Broadway Records]

Beyond The Headlines

A coal-fired power plant in Utah. (Photo: Doc Searls, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, let’s take a look behind the headlines now with Peter Dykstra. He’s an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. On the line now from Atlanta - Hi there Peter, what’s going on?

DYKSTRA: Hi Steve. The Trump Administration is preparing what appears to be an absolute smooch-fest for the coal industry. As you discussed with Dr. Landrigan, one of the big things that’s in the works is relaxing the rules on mercury emissions from coal-burning power plants.

CURWOOD: Mercury is such a neurotoxic, it’s really bad. It gets into lakes, it gets into fish, it gets into pregnant women. Not a good thing.

DYKSTRA: It’s a clear-cut health risk. The industry says it’s a major factor in the decline of the coal industry since it would cost a lot to retrofit plants to reduce mercury emissions. Environmentalists and health experts say that those costs to the coal industry would be mostly offset to the general public in the form of reduction of healthcare costs.

The Sutton power plant coal ash spill in North Carolina was the result of Hurricane Florence floods. (Photo: Waterkeeper Alliance Inc., Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: And of course, also having healthier people. What else is going on?

DYKSTRA: Well, here’s another one. One would think that after the coal ash spills that happened from Hurricane Florence, it might be a really bad time for the industry push to relaxed regulations on coal ash dumps. Those are the essentially toxic waste dumps of burnt coal that exist next to many of the operating and also the closed coal plants across the country.

CURWOOD: By the way, isn’t Andrew Wheeler, the acting EPA administrator, a former lobbyist for the coal industry?

DYKSTRA: Former lobbyist for the coal Industry. This is the kind of thing he would have lobbied for and now he’s being lobbied and apparently obliging the industry. Toxic waste from coal power plants would be exempt with what the industry is asking, from the very powerful Clean Water Act. They would also extend deadlines set by the Obama Administration for cleaning up the coal ash mess across the country.

CURWOOD: Okay, hey, what do you have from the history books today for us?

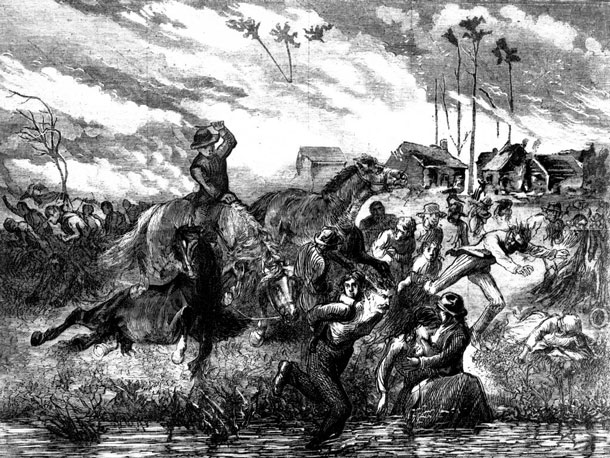

DYKSTRA: Let’s go all the way back to October 8th, 1871. The Peshtigo Fire was one of the biggest fires that day in arguably the worst fire day in American history. 2,000 people were believed to have died, when the town of Peshtigo -- a thriving Lumber mill town North of Greenbay, Wisconsin -- went up in smoke. There was another fire across Lake Michigan in the town of Holland, Michigan that same night, and also one of the most famous American fires, the Great Chicago Fire, happened that same night. 300 people died in that one.

CURWOOD: Now of course back then they said that Mrs. O’Leary had a cow that kicked over a lantern that started the great Chicago Fire. What do we know today?

An artistic rendering of the Peshtigo Fire incident featured in an 1871 edition of Harper’s Weekly. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

DYKSTRA: Well, Bart Simpson might say that Mrs. O’Leary had a cow when she heard that she was being blamed for the whole thing. They didn’t have busses yet but she was thrown under the bus along with her cow. There’s a lot of skepticism a century and a half later that that was the cause of the Chicago Fire. There’s also another theory out there that there was a meteor shower at that time in early October and that meteorites hit in the ground in places like Holland, Michigan, Peshtigo, and Chicago, causing all those fires. There’s a lot of skepticism about that theory too. More likely, it was a notoriously dry autumn in the upper Midwest and it was also a very very windy night.

CURWOOD: Yeah and that’s what we’ve seen recently in California. Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org, and DailyClimate.org We’ll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Alright Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And, you can find more about these stories if you go to our website, that’s L-O-E.org.

Related links:

- NYTimes | “Trump Administration Prepares a Major Weakening of Mercury Emissions Rules”

- The Intercept | “Hurricane Florence Released Tons Of Coal Ash”

- More on that deadly wildfire day in 1871

[MUSIC: TECH THEME]

Cool Fix For A Hot Planet: A Tiny, Carbon-Sucking Fern

Azolla is a tiny but fast-growing fern – and a voracious eater of carbon dioxide. (Photo: Richard Droker, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Coming up a failed tsunami warning system has a catastrophic impact in Indonesia but first this cool fix for a hot planet with living on Earth’s Anna Gibbs.

GIBBS: Scientists from Duke and Cornell Universities recently led a crowdfunding effort to sequence the genome of a tiny fern called Azolla. They had a hunch that the ancient plant could help cool down our planet - for a second time.

Fifty million years ago, the earth was hot and thick with greenhouse gases. Carbon dioxide levels were nearly ten times what we see today. Heavy rain flooded the coasts, palm trees sprouted in Antarctica, and the Arctic Ocean was like a warm lake.

Then along came Azolla. It thrived in the nutrient-rich air and soon covered the oceans like a thick green carpet. Though minuscule, with leaves smaller than a gnat, Azolla can double its entire body mass in less than two days. To do that it sucks up a lot of carbon dioxide, which makes it an excellent carbon sink. Within a million years, Azolla pulled trillions of tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. In fact, Azolla gobbled up so much carbon dioxide - nearly half the CO2 available at the time - that it helped cool the planet from an intense hothouse to the temperate climate we have today. Now scientists are researching the potential for Azolla to alter the climate once again.

The Azolla range in color from green to reddish-brown or purple at the edges. (Photo: bobistraveling, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

And if averting catastrophic climate change wasn’t enough, Azolla has another trick up its sleeve: it’s an excellent natural fertilizer. In fact, Azolla has been used to fertilize rice paddies in Asia for over a thousand years, and researchers believe it could be used on other crops to decrease the need for toxic synthetic fertilizers.

And the list doesn’t end there. Azolla has the potential to be a natural insect repellant and even a sustainable food source.

In any case, it seems Azolla may be able to lend us a hand - albeit an extremely tiny one.

That’s this week’s cool fix for a hot planet, I’m Anna Gibbs.

CURWOOD: And if you have an idea for a cool fix for our hot planet please send it our way and we might put it on the air. Our email address is comments at L-O-E dot O-R-G, that’s comments at L-O-E dot ORG.

Related links:

- Yale Environment360 | “Can A Tiny Fern Help Fight Climate Change and Cut Fertilizer Use?”

- The study in Nature Plants

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p4zj6nIPPXc Joshua Rifkin, “Magnetic Rag” on Scott Joplin Piano Rags, by Scott Joplin, Nonesuch Records]

Failed Tsunami Warnings

Palu, Indonesia, one week before the Tsunami hit, and again on the first of October, after the Tsunami devastated the area. (Photo: Courtesy of DigitalGlobe)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

The death toll keeps rising from the tsunami that recently struck Sulawesi, Indonesia. The deadly wall of water was generated by a 7.5 magnitude earthquake off shore. The Indonesian government installed a system of 22 buoys to help detect pressure changes related to the formation of a tsunami, but they haven’t been functional in years. And a new system to be anchored to the ocean floor and less vulnerable to vandalism was awaiting the green light for deployment when it was rejected for lack of funding just days before the most recent disaster struck. University of Pittsburgh political science professor Louise Comfort worked with teams of researchers in the US and Indonesia to develop an undersea sensor network to detect tsunamis. Professor Comfort joins us now -- welcome to Living on Earth!

COMFORT: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: So, what are the challenges that Indonesia has faced in preparing for extreme events like tsunamis?

COMFORT: Indonesia is in a very risk-prone environment. 17,000 islands and counting. It has a major earthquake over seven-point magnitude on the Richter scale every year, at least every year. It is vulnerable also to tsunamis and volcanic eruptions, so this is a major challenge for the country.

CURWOOD: And of course, what little more than a decade ago there was a huge catastrophic tsunami event there in Indonesia.

A man perched on a pile of wreckage after the tsunami in Aceh, Indonesia. (Photo: Photo RNW.org, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

COMFORT: Yes, 2004 a tsunami at the tip of northern Sumatra, Banda Aceh, and literally one in three people in that city were killed. I was there two and a half months after the tsunami, but seeing the devastation and still it was the stench of dead bodies two and a half months... it's just sobering. And it's this kind of experience that has made me so intent on trying to do what is possible to support decision making for the public managers that face these horrifying situations.

CURWOOD: So, I understand that the proposal to get these sensors installed in western Sumatra stalled, in fact, just a few days before this latest tsunami hit. I guess it was due to funding concerns? How did you react when you heard that news?

COMFORT: I was profoundly disappointed, profoundly disappointed. So, there are two parts to this project one is the undersea network that provides the initial near real-time warning, and then the second is the network of the electronic devices, essentially cellphones, handheld cell phones that enable people in the community to communicate as they evacuate or move to safer ground. We had planned to do the deployment this fall September-October. The Indonesian agency, BMKG, was very interested in this proposal. Unfortunately, the project is currently on hold until more funding comes in.

CURWOOD: So, it's like that everybody agreed that people should wear seat belts, but there wasn't enough money for everyone to have one.

COMFORT: Unfortunately, that's exactly the case.

CURWOOD: As I understand it, there was a system of buoys there to warn people about tsunamis. What happened to them?

Louise Comfort is a political science professor at the University of Pittsburgh. (Photo: Courtesy of University of Pittsburgh)

COMFORT: That's one of the painful parts of this project. Indonesia supported by the US and Germany had 22 buoys that were operating and designed actually to provide similar data from the ocean floor, a change in the water pressure in the water column. But those buoys actually had been vandalized and were not functioning, and as a matter of fact, the marine survey agency, BBPT, that manage the buoys, actually cancelled that program because they were not able to keep them operational. So, the buoys had not been operating since 2016.

CURWOOD: Now, what are the advantages of the system that you've helped to develop over this now defunct system of buoys?

COMFORT: The major difference is it is anchored to the ocean floor so it cannot be vandalized, and it uses a very interesting scientific phenomenon of the thermocline of warm equatorial waters to enable acoustic communication that is underwater communication where the data is transmitted from the sensors to another communication center to another communication sensor and then picked up in transmitted via cable to a land station that transmits the data via satellite.

CURWOOD: And of course, acoustic communication in the water is what the whales use.

COMFORT: Yes, exactly. That's exactly right.

CURWOOD: To what extent has the perspective now of the Indonesian government changed given this recent disaster?

COMFORT: Well, I hope it has changed. Right now, I'm certain that their full attention is on the immediate recovery, but I do hope that the agencies will reconsider this as a very important part of their overall tsunami early warning system.

CURWOOD: Louise Comfort is a professor at the University of Pittsburgh. Thank you so much for taking time with us today.

COMFORT: Thank you. It's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- NYTimes | "How to Help Survivors of the Indonesia Earthquake and Tsunami"

- Associated Press | "Warning system might have saved lives in Indonesian tsunami"

- Al Jazeera | Indonesia Earthquake and Tsunami Updates

- An archive of satellite imagery from before and after the storm

- Louise Comfort Faculty Profile

[MUSIC: Qingxi, “Journey” on DJ Sun, Soular Productions]

Walrus Changes His Mind

Walruses laze out on the beach. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Svalbard archipelago in Norway is a rugged frozen landscape near the Arctic Circle that’s home to polar bears, reindeer and walrus. As Living on Earth’s explorer in residence Mark Seth Lender explains he recently had an up close, maybe too close for comfort encounter, with a 3000-pound walrus.

LENDER: A finger of glacial till points into the fjord; on Svalbard at Poolepynten point, where the walrus haul out. The place is low but the slope is steep, for a walrus, and once the effort is made the herd prefers to stay there.

Do Not Disturb.

That is all they want.

They drowse. And stretch. A flipper like an open hand reaches into the air as if making shadows on a non-existent wall. Scratches the chin... the cheek…. then lets the hand fall. The walruses in their tans and browns all blending into the land where they recline.

Out in the frigid water a walrus head appears. Tooth Walker, his Walking Teeth strong where they show above the water and lined along the length of them with crevices and ivory-bright. His wrinkled skin like a parchment map of all the places he has been, shows his age, and the bulk of him a measure of his station. He paddles unconcerned towards Poolepynten. Runs aground. Rests. Then continues, laboring up the slope under the load of his greatness.

A walrus eyes his observer suspiciously. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

From the midst of the herd another walrus raises his head in greeting, the meeting of their eyes a nod of recognition.

And the small waves break against Tooth Walker’s chest.

All as it should be.

And then Tooth Walker sees… me.

What? What!

He leans. He looks.

The eye that was soft and dark grows wide, then soft (not sure of what he’s seen), then on the double take, wide again!

And turns back!

And out he goes!

And his breath blows!

He finds his draft and swims.

Shumph! Sharumph!

Towards me.

Rump humph!

At speed on short strokes below the surface that cannot be seen.

And grounds.

Fumph!

Close.

Walruses possess distinctive tusks that can grow up to a meter in length. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

And comes closer.

Fumf farumph!

And stops, and lifts, and shows his tusks!

He looks, both sides, from his left to his right.

And…

Lowers his head.

But changes his mind! Up! The ring around the white of the eyes blood red!

And…

Subsides.

And turns away…

Tooth Walker swims, returning as he came, through the sea. Then pulls, and tugs, and lugs himself out. Rejoining the herd, they raise their tusks to him and he greets them one by one. But again, and again, his gaze returns to let me know: He has not forgotten exactly where I am.

Having seen Tooth Walker and his Walking Teeth, up close? He has nothing to worry about. Not from me.

CURWOOD: Mark Seth Lender is Living on Earth’s explorer in residence, and there’s more on our website LOE.org

Related links:

- Mark Seth Lender’s Website

- One Ocean Expeditions

[MUSIC: Eric Tingstad, “Long Boats” on Mississippi, Cheshire Records]

Hemlock Trees On Hospice

Title: “Hemlock Hospice Forest Lantern, No. 2,” installation at Harvard Forest, 2 x 4 x 5 feet, wood, acrylic paint, vinyl, and assorted hardware, 2017. Collaborators: Jackie Barry, David Buckley Borden, Dr. Aaron Ellison, Tim Lillis, and Lisa Q Ward. (Photo: courtesy of David Buckley Borden)

CURWOOD: The Harvard Forest in Petersham, Massachusetts is known as the “wired woods.” It’s a hotspot for scientific research on topics ranging from soil warming to atmospheric carbon exchange. And now a researcher has created an art exhibit in the forest. The work, called “Hemlock Hospice,” is a joint effort between ecologists and artists to tell the story of losses among the Eastern Hemlock trees, once giants of the lumber business. Living on Earth’s Savannah Christiansen went to check it out.

[SFX Birds chirping, Hemlocks creaking]

CHRISTIANSEN: At first glance, the Harvard forest looks like a typical New England forest. Birds chirp in the branches above and the sun shines in a perfectly clear sky. But look more closely, and you notice all the hemlock trees are dead or dying. An invasive species is killing them off by sucking out their sap. Spindly, bare branches are strewn about the ground. And the decaying, gnarled trunks moan as they lean over one another.

Title: “Wayfinding Barrier, No. 1,” installation at Harvard Forest, 2 x 3.75 x 4 feet, wood, acrylic paint, vinyl, hardware, aluminum tape, and recycled field equipment (heat lamp and ant nests), 2017. Collaborators: David Buckley Borden, Jack Byers, Aaron Ellison, and Salua Rivero. (Photo: courtesy of David Buckley Borden

[SFX Hemlocks creaking]

CHRISTIANSEN: This part of the forest houses an art installation project created by David Buckley Borden, the Harvard Forest’s artist-in-residence. The project is called “Hemlock Hospice.”

BORDEN: As most folks know, hospice care is end of life or end of term care. And it's designed to have a more dignified close to one’s life, but it’s also intended to benefit the living, so they can have a positive experience, as much as one can, when experiencing the loss of an individual or a species or an ecosystem.

CHRISTIANSEN: Borden teamed up with Harvard Forest’s senior ecologist, Aaron Ellison, for the project.

ELLISON: Mostly, I study how ecological systems fall apart and then how they put themselves back together again.

CHRISTIANSEN: This ecosystem first fell apart more than 300 years ago.

ELLISON: This was an old growth forest when Europeans showed up in this landscape in the 1600s and early 1700s. So, you have big trees and very small people. And they didn’t have chainsaws, they didn’t have power tools, but they had a lot of strength and a lot of willpower to make it something that we could use. And they very assiduously cut down all the forest.

CHRISTIANSEN: Over time though, eastern forests, including hemlock trees grew back and today, there’s actually more forest cover in New England than there was in the colonial days. The hemlock’s modern troubles started in 1951, when an insect called the hemlock woolly adelgid was introduced in Virginia.

[SFX trail walking sounds]

Aaron leads the way along a trail to see the artistic interpretation of the adelgid’s impact on the hemlock forest.

ELLISON: This is what we call “Insect Landing.” And it’s an abstraction in lots of different ways of perhaps an insect colonizing our forests, perhaps a spaceship. It's a yellow diamond with a white x in the middle of it and it's made from recycled materials. It's made from fence rails that would be around a porch on one of our houses that Harvard Forest has, it would have been salvaged from that.

CHRISTIANSEN: Again, artist David Buckley Borden.

Title: “Hemlock Memorial Woodshed,” installation at Harvard Forest, 8 x 8 x 9 feet, wood, acrylic paint, and assorted hardware, 2017. Collaborators: David Buckley Borden, Mike Demaggio, Aaron Ellison, CC McGregor, Jared Laucks, and Lisa Q Ward. (Photo: Courtesy of David Buckley Borden)

BORDEN: Well in terms of the narrative, this piece is really the prompt to talk about introduction of the insect. So, we talk about how the insect was introduced on nursery stock from Japan in the 50s and how over the course of the last 40, 50 years it slowly migrated north with climate change. You know, people often talk about climate change in terms of the big storms, rising tides, mega fires, and they’re all valid, but this is just as impactful, but it’s kind of a slow creeper, if you will.

CHRISTIANSEN: The adelgid has left a wake of dead hemlocks from Georgia to Maine, and will continue marching north as climate change creates new habitats for it. Already, its reached southwestern Nova Scotia.

[SFX Hemlocks moan, footsteps]

CHRISTIANSEN: We keep walking, and find the next installation strung up high in the canopy between two hemlock trees.

BORDEN: So, what you see is essentially a stylized tent hanging about 30 feet in the air. On the side of it you would see about 12 to 13 states represented. And those are all the states in which the insect is now in, up and down the east coast.

CHRISTIANSEN: But Aaron says the tent holds a deeper meaning about the invasive insect.

ELLISON: When we use language like invasive species we are attributing agency to the insect or the plant or the animal that is invading. But in fact, it really doesn't have agency. The insect came on nursery stock that we imported. And then the insect does what any immigrant would do. It says I’m here, I’ve got to eat, I’ve got to have a place to live and a place to make a better life for my offspring. And so, for me it’s a good way to talk to people to get them to think about, well what are you really thinking about when you go after an invasive species or when you label something as an invasive species?

CHRISTIANSEN: Aaron says the installations are here to get both visitors and scientists thinking about these issues. Back in 2004, researchers tried to mimic the way adelgid kills hemlocks, to see how the ecosystem would respond.

ELLISON: So, we took chainsaws and knives, and we cut rings around the bark and into the wood to cut off the flow of sap. And in these two experimental plots, we killed about 2,000 trees in 45 minutes.

CHRISTIANSEN: The results are printed on the side of a woodshed. It’s a graph that reads “Lifeline of a Dying Hemlock.” The plummeting red and black lines depict the amount of sap running through a Hemlock trunk.

Aaron Ellison is the senior ecologist with the Harvard Forest. He is also an avid photographer and writer. (Photo: Flossie Chua)

ELLISON: And the graph that’s in front of us shows us the difference in sap flow between a tree that we didn't cut and a tree that we did cut. And it's just like watching an EKG of someone in the Intensive Care Unit as their heart rate goes down.

CHRISTIANSEN: And that got Aaron thinking about the ethics of his work.

ELLISON: I like to try and use this as a way to talk to my scientific colleagues about how you really have to think about what we are doing to the organisms we study. We killed these trees to understand how this forest will respond. We learn a lot by doing that. We respect what we're doing, we publish our data, that’s how it gets out. But we do have impact on our forests in order to understand this.

CHRISTIANSEN: As we come to the end of the walk, David and Aaron stop in front of one of the last installations. It shows the future of this forest: a mossy hemlock stump and next to it, a healthy black birch tree. Ecologists believe birches will one day replace Hemlocks here. These woods will change, and it won’t look like colonial settlement or the hemlocks’ death bed. But David and Aaron hope Hemlock Hospice will create a space for visitors to remember the Hemlocks long after the exhibit ends. For Living on Earth, I’m Savannah Christiansen in the Harvard Forest in Petersham, Massachusetts.

Related links:

- The Harvard Forest: “Hemlock Hospice”

- The closing reception for Hemlock Hospice event page

- Learn more about Aaron Ellison’s work

- David Buckley Bordon’s Website

[MUSIC: Eric Tingstad, “Tennessee Rain” on Mississippi, Cheshire Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up, Former Secretary of State John Kerry on his love for the ocean and how best to protect it. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast. listen at race to nine billion dot com. That’s race to nine billion dot com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Eric Tingstad, “Skamania” on Mississippi, Cheshire Records]

John Kerry Looks Back – And Ahead

Secretary John F. Kerry talks about his 2018 memoir Every Day is Extra with Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

John Kerry is looking confidently into the future, even as he reflects back on a life in public service, which ranges from being the face of Vietnam Veterans Against the War to a Democratic nominee for President and Secretary of State. Secretary Kerry writes about challenges facing the world, focusing on climate change in the final chapter of his 600-page memoir titled Every Day Is Extra. And even in the face of President Trump’s opposition to climate action, John Kerry remains optimistic. He spent his youthful summers in and on the waters of Buzzards Bay in Massachusetts, which gave him a lifetime attachment to the sea. Over the decades he’s played key roles in legislation and international negotiations on climate change, acid rain, and ocean health. Secretary Kerry, welcome to Living on Earth!

KERRY: Happy to be here. Thank you.

CURWOOD: So, if there's one thing from your book "Every Day is Extra," it is your love of the ocean why does the ocean call to you in such a strong way?

KERRY: Well, I'm a son of Massachusetts I think it calls to all of us, sons and daughters. We are blessed to be people of the sea here in the state of Massachusetts and we love Cape Cod, we love the islands, and I learned as a kid. I was raised around Buzzards Bay and I used to just clam and fish and play in the water, learn how to sail, do all these wonderful things. But I learned about under the water, and I then was a big Phillip Cousteau fan and used to tune in. My mother was in the enormous conservationist and environmentalist, and I grew up with a sense of responsibility understanding that the ocean is fragile. It's not impervious to the things we humans do to it.

CURWOOD: And as I recall from your book, in your fortunate childhood, you were on one of the Elizabeth islands, you were on Naushon.

Above, sailboats docked at Hadley’s Harbor on Naushon Island. Kerry’s love of the ocean was shaped in part by summers spent on the seven-mile-long island just off Cape Cod. (Photo: Putneypics, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

KERRY: Yeah.

CURWOOD: And then you come out of Woods Hole and you can see it on your way to Martha's Vineyard if you like. It's a great place to have your toes in the sand as a kid.

KERRY: Yeah, it's a gift beyond description, and it was wonderful to be able to be there, but I think that everywhere on our Cape, people would get to experience the beauty of our sand dunes, of our low tides, of the enormous beaches, the remarkable vision that President Kennedy had to keep great Cape Cod seashore national monument. So, we're very lucky people and our history goes way back. Obviously, I mean everybody during the era of 1700s, 1800s, early 1600s came here on a boat, and we have always had a tie in our history to the sea. In our merchant efforts, the China trade...

CURWOOD: The cod on top of the statehouse.

KERRY: The cod, whaling. And you know we don't have cod now. I mean, this ought to be a message to everybody. It's Cape Cod but there are no cod...or very very few and precious few, and it's a tragedy if we don't start paying attention to how we manage these kinds of things. We could see an economic impact on our state.

CURWOOD: So, what do we need to do today to take care of our oceans?

KERRY: I think there are three primary challenges: number one climate change, which is caused by greenhouse gases which fall in the ocean and acidify the ocean which has a negative impact on the growth of clams, crustaceans, shells and bleaches out spawning grounds and coral reefs and so forth around the world. We don't know all the impacts. We know it has an impact. We don't know the rate of impact. We don't know where you could have a precipitous catastrophic impact, and so that's why we owe it particular respect and concern.

The second great impact is pollution, general pollution. People build. They build near the ocean. There's what we call non-source point pollution. You have runoff, you have gasoline runoff from stations, you have oil runoff, you have pesticide runoff, you have high nitrate runoff which affects the level of oxygen in the water, and therefore the fish and plants and fauna in the ocean, and we have 500 dead zones around the world in the oceans today, dead zones, nothing grows because of what has happened with this overload. And also, pollution generally, effects the fish, you have plastic getting into marine mammals into birds. I've seen film of sharks and or porpoises and or whales dragging nets around and dragging plastic around. It's crazy.

And then finally, we have overfishing. We have too much money chasing too few fish and that's one of the reasons that we don't have cod anymore here. Eight of the top fisheries of the world are now overfished, out of the sort of 18 or so fisheries, principal ones, and the others are at or near max. So, with 450 million Chinese who have come out of poverty into the middle class who now have discovered blue tuna and sushi, with 400 million Indians likewise and people around the world gaining in income and therefore appetite, we have a huge challenge, and already about 12 percent protein that people get in the world comes from fish, so there's a huge demand for fish as a food stock and increasingly we're going to see pressure on that. So, those are the biggies, but the pollution is just stunning. I mean, if we continue at the rate we're going, there will be more plastic than fish in the ocean in 20, 30 years.

Former Navy Lieutenant John Kerry spoke out against the Vietnam War as part of VVAW (Vietnam Veterans Against the War) during his testimony before the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee on April 21, 1971. (Photo: AP Images/Henry Griffin)

CURWOOD: Now, of course, you've had a storied career most recently as a diplomat. In your background, I think you spent some time in France and Switzerland as a kid, your dad was a diplomat. But when it comes to the ocean you've had some special concerns, and I just want to quickly ask you about two. One there's something called the Law of the Sea Treaty. It was something that the United States and folks from Massachuetts just like Elliot Richardson worked on years ago which we've never ratified. And now there's talk of having some sort of a high seas treaty that would govern...what is half of the world that is not in any jurisdiction.

KERRY: Correct, it's called the high seas, and the high seas do not belong to any particular nation, but they get egregiously overfished by renegade fishers, pirate fisherman, and years ago Senator Ted Stevens and I went to the United Nations to try to ban the driftnet fishing. We succeeded, it was banned, but today you have pirate fishermen, renegade fishermen, who go out with a draft net and a drift net is literally thousands of miles of monofilament netting that they drop behind the boat, drag along. It kind of strip mines the ocean and as much as two-thirds of the catch, certainly 50 percent, is called waste catch. They just throw it overboard. So, it's changing the ecology of the ocean by...imagine the vision of you see a strip mine on coal or the land, you see it just ravaging everything around it. This is what a driftnet will do and then sometimes it breaks off and it becomes what we call the ghost net because it just fishes on its own. When it's weighted down with carcasses, it sinks to the bottom and scavengers clean it off, and it rises to the top again until it gets tangled in a whale or tangled in the propellers of some boat. It's a scourge and we have no enforcement on those high seas or very little enforcement, I should say, occasionally someone's military ship goes through it and you can check on who's who and what's happening and you can certainly mark what ships are there fishing.

Kerry says, “If we continue at the rate we’re going there’ll be more plastic than fish in the ocean in 20, 30 years.” (Photo: rey perezoso, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, we're overfishing. Talk to me about the climate and your concerns about climate change.

KERRY: We face a massive challenge of dealing with climate refugees. The prime minister of the Fiji Islands, I just met with him the other day at an event in California where he pointed out that there are literally taking refugees from other islands, and they themselves are now planning how to move, where can they go to be safe. They are going to lose their nation state which is these islands. Increased fires, increased floods, more moisture in the air because of the warming of the ocean, more intensity in the storms because of that moisture we're seeing it in the hurricanes. We've seen last year just three hurricanes - Harvey, Irma and Maria - cost the taxpayer $265 billion dollars, one third of the Defense Department budget for a year. Think of that. Three storms and it's going to get worse, so people who sit there and say well we can't afford to do something or we can't it's crazy, it is far more expensive to do nothing or to do very little than to actually step up and try to deal with the problem of climate change. And why? Because the answer to the problem of climate change is energy. Energy policy. We have the solutions. Solar today is less expensive than coal, but people are still using coal. We shouldn't be. We can't be using coal because it's the dirtiest fuel there is, and we've got to move off of coal on to the alternative renewables. They’re there, and we need the leadership that does it and regrettably this president and his administration and not only not dealing with climate but they're lifting the restrictions we have on air quality because of automobiles. They're lifting the restrictions we had on coal dust going into water, into rivers and lakes. They're putting it back. God knows, I don't know who the constituency is for this, but that's what they're doing. Well...you do know the constituents. It's coal companies and it's big corporations and so forth, and we have to fight back against it.

CURWOOD: Your book, which you call "Every Day is Extra" could almost be about the climate itself, that every day we wait to deal with it.

Every Day Is Extra caught public attention on the New York Times Best Seller List. (Photo: Courtesy of Simon & Schuster)

KERRY: Well, it is about the climate. The last chapter of my book, which I'm very partial to, it's the wrap up chapter, is called protecting the planet, and I deal with my efforts to get the Paris agreement passed. I mean, I went to China, brought the Chinese into the agreement with us because I watched the failure in Copenhagen four years earlier where it fell apart because China was leading the less developed countries in a different direction. China and the United States were able to lead the world to make an agreement, that's what we have to get back to. Instead of bashing China every day with new sanctions - now there are problems with China's management of the market - I'm not ignoring that but I think there's a better way to deal with it than the current administration.

CURWOOD: So, let's drill down on that. I believe over the years I've seen you just about every of the major climate conferences. What inspired you to think that you could find a way to cut a deal with the Chinese? Because between us and the Chinese, what, it's 40, almost 50 percent of the world's emissions...

KERRY: Well, sort of just shy of 50. It's about 45 percent.

CURWOOD: Yeah, so what inspired you to think that there would be a way that you could get them to join us?

KERRY: Because I believe in logic. I believe in common sense, and I believe in the power of persuasion, and I believed that it was in China's interest. I mean it's hard to get countries to do things that they never perceive are in their interest, but I thought it was in their interest because I had spent enough time working with lower level Chinese bureaucrats on the subject of climate. I knew what they were thinking and I knew they were hearing from their own constituencies. I mean China is a one-party system, it's authoritarian, yes, but it's not immune to citizen opinion, and it's quite amazing really the way, in fact, it filters up through the mayors and the governors and into the ether of their politics. So, I was hearing from people that Chinese were increasingly upset with the quality of their water. They're upset with the quality of their air. We were posting the daily air quality on the embassy in Beijing, and people were tuning in like crazy to our embassy to find out what the air quality was, and the Chinese didn't love it, but we did it. It had an impact, so they wanted to take care of their people. It's that simple. They really knew, but they did it because politically it's survival. They knew it was important to their ability to be able to meet the people's interests, which is basic politics. We haven't been doing that in America by the way. People's interests are not being met in our own country, and that's why our democracy is in trouble. That's a whole different diversion will go there in this instance.

CURWOOD: Well, but do go there.

Kerry and his wife Teresa at a rally in Portland, Oregon in the final months of his campaign for President on August 13, 2004. He lost the election to incumbent President George W. Bush by a popular vote margin of 2.4%. (Photo: Getty Images / Hector Mata)

KERRY: It has to do with whether we get things done on the environment, whether we hold people accountable to what's happening now. The fact is that I believe people, individuals and kids here at UMass or at any college in this country are the key to being able to hold politicians accountable. And you can't do it sitting on your butt pretending somebody else is going to do it or it does not involve you. Everybody has to be involved in this. We have to go out and organize and make a difference. So, why do I say this with such conviction? I'll tell you why. Because we did it in 1970. In 1970, Rachel Carson had inspired many of us with the Silent Spring". We had the Woburn waste dump with toxic waste sites, we had a river, the Cuyahoga River in Ohio would light on fire literally, and people said I don't want to live next to this, I don't want to get cancer from the water I drink, I don't want to get emphysema or heart disease from the air quality.

So, we brought 20 million Americans out of their homes on one single day, Earth Day April 22, 1970, and we translated that into a political movement. We targeted the 12 worst votes in the United States Congress House of Representatives. Seven of the 12 lost their seats in the '72 election. And guess what? Boom, we had the Clean Air Act passed, the Safe Drinking Water, the Marine Mammal Protection, the Coastal Zone Management. The EPA was created and Richard Nixon signed it into law. Why? Because it was a voting issue. That's what we have to do today folks. There's no mystery to how we reclaim the direction and future of our country. It's by going out and working in our democracy, make it work. Last time in 2016 when Trump was elected, 54.2 percent of eligible voters came out to vote, 54.2. When Barack Obama was elected in 2008, it was 62.3 percent. That's the difference. The story of what we have today is not the people who did vote. It's people who didn't vote, and so I'm just saying to you we can change this but we have to do it now because the clock is ticking.

CURWOOD: John Kerry is a former Secretary of State, Candidate for President, a five-term United States Senator for Massachusetts, and his new book is called Every Day is Extra. We’ll have the rest of our conversation with Secretary Kerry next week, and you can find the full interview on our website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Every Day Is Extra

- U.S.-China Joint Announcement on Climate Change: Nov. 12, 2014

[MUSIC: BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: Chipping Sparrows: Song Learning Starts Early

The Chipping Sparrow can be easily identified by its orange-colored cap. (Photo: Mike Hamilton)

CURWOOD: Our beloved songbirds are getting ready to make their way south again for the winter. As Birdnote’s Mary McCann tells us, this is actually an important time of year for young birds to learn the songs that will help them survive and ultimately find a mate next spring.

[Chipping Sparrow song]

Few songbirds are more familiar across North America than the Chipping Sparrow.

[Chipping Sparrow song]

Petite and rufous-capped, Chipping Sparrows breed over much of the continent. They winter in the southern U.S. and Central America. Yet familiar as the birds may seem, scientists are still unlocking their secrets. Recent research shows that when baby male Chipping Sparrows beg for food, their first begging calls already show a connection with the songs they will develop.

[Chipping Sparrow begging calls]

A Chipping Sparrow in song. (Photo: Tom Grey)

Soon, the young males’ begging calls mix into what is known as “subsong,” a sort of infant babbling for young male birds. And, very quickly, subsong begins to transition to imitations of adult songs. By the time a young male Chipping Sparrow migrates south in early October, it has developed five to seven “precursor songs” – works in progress, but closer to adult songs. Next spring, when the young male returns north for its first breeding season, it will settle in near an older male. Soon it drops all but one of the precursor songs – the one most like the older male’s song – and in a few days, nearly matches its neighbor note for note.

[Chipping Sparrow song]

Then for the real test of its new song – attracting its first mate.

[Chipping Sparrow song]

I’m Mary McCann.

Chipping Sparrow begging call provided by Borror Laboratory of Bioacoustics, Department of Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, all rights reserved.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2012 Tune In to Nature.org October 2018 Narrator: Mary McCann

CURWOOD: For photos of the chipping sparrow migrate on over to our website L-O-E dot org.

Related links:

- Learn more on the BirdNote website

- The Cornell Lab of Ornithology -- Chipping Sparrow

[MUSIC: Greg Abate Quartet, “Motif” on Motif, by Greg Abate, Whaling City Sound]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Thurston Briscoe, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Sarah Rappaport, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari.

Special thanks this week to One Ocean Expeditions.

Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I’m Steve Curwood, Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong clean energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth